2030: War in the Shadows: How China Could Take Taiwan Without Firing First

The first sign was not a missile launch, but a picture.

At 06:42 Taipei time, a high‑resolution satellite image surfaced on a public imagery feed: a line of grey hulls pushing east from the Chinese coast, wakes cutting clean V‑shapes through the strait. Amateur analysts on X matched silhouettes to PLA Navy amphibs. Others fixated on the squat, boxy shapes riding low in the water. They were not ferries. They looked like the new barge‑like ships that OSINT analysts had tracked in Guangzhou that spring, built to plant a pier at sea and roll heavy kit ashore where defences were thinnest.

Four minutes later, Taiwan’s Ministry of National Defense accounts went quiet. Along the west coast, fishing crews radioed that trawlers with unfamiliar antennae were loitering along key approach corridors to Taiwan’s western ports. At 06:53, parts of Taipei and Taichung lost power. Metro lines stalled. In Hawaii, secure feeds at Indo-Pacific Command lit up with alerts of unusual low-Earth-orbit manoeuvres by Chinese satellites. These movements looked like co-orbital approaches to allied eyes. No explosions. Just a spreading sense of isolation. The game was to blind and paralyse before anyone said the word war.

How we got to 2030

What follows is a fictionalised scenario, drawn from current trends and military analysis. The events described have not happened. Yet the regular presence of Chinese aircraft inside Taiwan’s Air Defence Identification Zone, the tempo of naval drills in surrounding waters, and the increasingly assertive rhetoric from Beijing all offer raw material for thinking about how such a crisis might unfold.

In this imagined 2030, the assault was not improvised. Beijing’s military thinking for a Taiwan contingency had long centred on systems-destruction warfare. The aim was to identify the handful of critical nodes that let an opponent sense, decide and act, then break those links so thoroughly that the rest of the system collapsed under its own weight. It blended electronic warfare, cyber operations, deception and precision strike, leaning heavily on the space layer because that was where modern command and reconnaissance lived. By 2030, this concept had migrated from journals and staff colleges into force design and training.

Washington and its partners had not been idle. Over the preceding years, the United States had strengthened access agreements and forward logistics across the first island chain and beyond, expanding the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA) footprint in the Philippines, a network of U.S.-accessible sites positioned within rapid reach of the Bashi Channel and Luzon Strait. At the same time, Washington deepened operational cooperation with Japan, Australia and other regional partners. The aim was to reduce deployment times, multiply the launch points for a response, and complicate PLA planning to the point that any attempt at a swift fait accompli would face several unpredictable and mutually reinforcing axes of resistance.

There was also a timeline in mind. U.S. commanders had long warned that Xi Jinping wanted the PLA to achieve full capability for a Taiwan operation by 2027, a planning milestone rather than a fixed date for action. By 2030, those capability targets had been met against a backdrop of rising domestic pressures inside China and a more contested regional information environment. The strategic window appeared to be open, but it was neither unlimited nor without risk for Beijing.

The opening front is in orbit

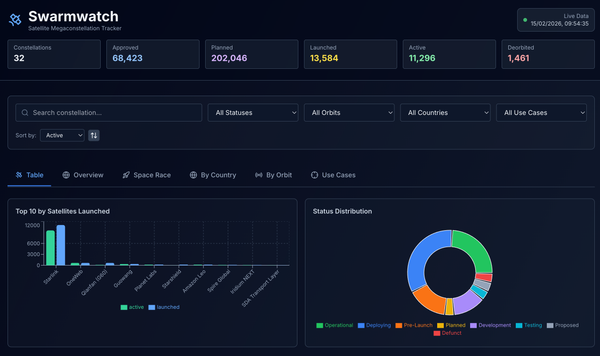

The first moves aimed to blind. Ukraine had already shown how commercial space could be decisive, where low‑latency constellations kept units connected, sensors fused, and targeting data flowing even under heavy jamming. It also showed the political and technical fragility of relying on a single private network. A Taiwan fight would draw the same lesson. Expect cyber pressure on ground stations, targeted interference against LEO user terminals, and close‑proximity manoeuvres that spook or spoil allied ISR capabilities.

China had already demonstrated precise co‑orbital capability. In 2022, Shijian‑21 docked with a defunct satellite in geostationary orbit and towed it to a graveyard slot. Advertised as debris mitigation, it nonetheless proved a skill set that worries planners when space is the nervous system of modern war. Even a small number of such manoeuvres forces costly defensive reactions and injects doubt into already compressed timelines.

This is also where the nuclear shadow creeps in, without taking over the story. Some of the satellites and data links that enable conventional targeting also support early warning and elements of nuclear command and control. Aggressive counterspace activity risks being misread as strategic preparation, especially under pressure. Escalation is not inevitable, but misinterpretation becomes easier when your adversary is deliberately degrading your picture.

The barges and the grey fleet

While global attention tends to focus on China’s high-profile carrier groups and big-deck amphibious assault ships, the more transformative innovation has been quieter and humbler. In 2025, open-source analysts identified a surge in the construction of Shuiqiao-class landing barges, followed by beach trials demonstrating their ability to create a temporary causeway from deep water to the shore. These vessels are simple, modular and cheap enough to build quickly in large numbers. Their design makes them complex to track at scale because they can be dispersed across multiple civilian ports and blended into commercial traffic patterns until needed.

The tactical utility of such barges lies in their ability to bypass the handful of obvious, well-defended landing beaches. By creating improvised access points along less prepared stretches of coastline, they complicate Taiwan’s defensive calculus. Any segment of shoreline becomes a potential landing site, forcing defenders to spread finite resources more thinly and diluting the effectiveness of concentrated firepower. This turns the problem from defending a few known approaches into defending dozens, each of which may be exploited simultaneously or in rapid sequence.

These barges fit seamlessly into China’s broader maritime strategy. They pair neatly with the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia, a vast network of ostensibly civilian fishing vessels that can be tasked with reconnaissance, logistics and even harassment of enemy forces. They also integrate with militarised roll-on roll-off ferries that can deliver heavy vehicles, armour and supplies in bulk once a beachhead is secured. In an integrated campaign, this layered approach to amphibious lift combines high-end assault ships for spearhead landings with the grey, civilian-facing fleet for follow-on sustainment and dispersion.w

In this way, the barges are not a standalone capability but a critical enabler of a broader operational concept. When used alongside space-based reconnaissance to time their movements and cyber operations to blind defenders, they help transform the Taiwan Strait from a narrow, predictable crossing into a multi-directional, multi-domain assault corridor. The result is a physical capability that complements the PLA’s digital and orbital pressure, creating a more resilient and adaptable invasion architecture.

Cyber first, then fire

Before the first missile flies, the pressure is digital. The target list writes itself: power distribution, rail signalling, air traffic control, hospital networks, payments, and media. The aim is not permanent collapse but to slow mobilisation, sow doubt, and force the government to spend precious hours on triage. Those hours matter more than days in a campaign designed to be fast, decisive, and multi-domain.

The methods are varied. Malware seeded months or years earlier through compromised supply chains can be triggered in sequence to cause cascading failures. Coordinated botnet activity can drown emergency lines and overload official communication channels. Deepfake leadership statements, timed to coincide with real disruptions, erode trust in legitimate orders. Spoofed emergency alerts can send civilians in the wrong direction or flood key routes with panicked traffic. Financial system friction, from frozen ATMs to delayed clearing of electronic payments, erodes public confidence and constrains logistical purchases.

This cyber blitz is not just about what happens on the island. Attacks against allied infrastructure, cloud providers, undersea cables, or regional data centres can create ripple effects that slow outside help or complicate coordination. Well-timed campaigns can generate uncertainty in allied capitals, making decision-makers hesitate while they confirm the facts. If paralysis takes, the kinetic phase can be shorter and sharper. If not, Beijing can shift into blockade mode, using the same digital tools to maintain constant low-level disruption, paired with selective strikes and naval manoeuvres that keep pressure on without crossing escalation thresholds too quickly.

Maritime and air integration

When the curtain lifts, it is about mass and denial. Amphibious ready groups and merchant conversions advance under a layered canopy of counter-air and counter-maritime fires. Long-range anti-ship and land-attack missiles target choke points, staging areas and any allied naval formations approaching the battlespace. The aim is to keep U.S. carriers, surface combatants and key logistics vessels outside the useful radius where they could disrupt landings or provide sustained fire support.

Systems like the DF-26 family matter here. Officially designated the Dong Feng-26, it is a dual-capable intermediate-range ballistic missile with both land-attack and anti-ship variants, able to carry either conventional or nuclear warheads. Its range of roughly 4,000 kilometres allows it to strike targets well beyond the first island chain. This versatility makes signalling far more difficult, since the same launcher could be preparing a conventional strike or a nuclear one. That ambiguity is deliberate, designed to complicate targeting decisions and compress the opponent’s decision cycle in a crisis, forcing them to divert resources to protect against the worst-case scenario.

In the air, the invasion is fronted by waves of PLA Air Force and PLA Navy fighters operating from multiple directions. These waves are not simply large; they are sequenced to exhaust defenders, with early sorties probing for air defence coverage, later ones delivering stand-off strikes, and others sweeping to secure air corridors for the slow-moving amphibious convoys. Each wave is supported by airborne early warning and control aircraft, tankers for extended loiter time, and electronic warfare platforms to degrade radar and communications. More capable unmanned systems act as loyal wingmen, flying ahead of or alongside manned fighters to jam sensors, launch decoys, or carry out kamikaze strikes on high-value defensive assets.

This air pressure is enabled by years of investment in “stepping stone” bases across the South China Sea and the Chinese mainland’s southern coastline. Artificial islands and fortified outposts in the Spratlys and Paracels provide additional runways, forward-deployed missile batteries, fuel stores, and radar coverage. These facilities, already defended by layered surface-to-air missile systems, extend the reach of Chinese air power into the Philippine Sea and complicate allied planning by forcing them to operate within overlapping threat envelopes.

Beneath the surface, unmanned underwater vehicles seed approaches with mines, shadow logistics routes and harass escort vessels. Submarines, both manned and unmanned, can act as mobile barriers, denying freedom of movement to allied ships attempting to reach the landing zone. The goal across all domains is to create a shifting, layered bubble of denial that moves with the amphibious groups, protects the crossing and buys critical time ashore for follow-on forces to consolidate and expand the beachhead.

Holding allies at arm’s length

The alliance problem is time. The United States and its partners have increased access points and pre-positioned more equipment. Still, the decisive factor remains how quickly political leaders authorise their use and how rapidly those forces can traverse the region’s geography. Dispersed EDCA sites on Luzon shorten flight legs to the Bashi Channel and the Luzon Strait. At the same time, Japanese and Australian basing options provide flanking routes for intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR), aerial refuelling and long-range strike missions. In theory, this network can generate converging pressure on PLA forces from multiple directions. In practice, it is only as effective as the political will and speed of coordination behind it.

The challenge lies in synchronising national decision-making cycles. In Washington, the choice to intervene could be slowed by congressional scrutiny, competing global priorities or the need to verify intelligence in a degraded information environment. In Tokyo, the constitutional constraints on collective self-defence mean any action will require political consensus and careful justification to the public. Canberra may be willing to move faster, but will weigh the risks of PLA retaliation against its critical infrastructure and maritime trade routes. Even if the intent to act is shared, mismatched authorisation timelines can produce a fragmented allied response, which is precisely the kind of delay Beijing would seek to exploit.

The fog in those opening days will not be limited to politics. Integrated warfare blurs the line between peacetime posturing and active hostilities. Cyber disruptions, spoofed communications and degraded satellite imagery could leave commanders uncertain about which targets are real and which are decoys. In such conditions, caution can feel safer than speed, even when the latter is strategically necessary.

Nuclear signalling amplifies this hesitation. China maintains its declared policy of no first use but is modernising at pace, with U.S. assessments placing its operational warhead count above 600 by mid-2024 and rising. In a Taiwan contingency, the United States would likely raise the alert level for ballistic missile submarines, ready bomber task forces and missile defence units to send a clear deterrent message. Japan and Australia, though non-nuclear, would immediately factor potential Chinese nuclear coercion into their calculations, especially if PLA Rocket Force units with dual-capable missiles like the DF-26 were observed dispersing to firing positions.

The grey zone here is not just in geography but in interpretation. A PLA co-orbital satellite manoeuvring close to a U.S. early-warning platform could be a test, a message or preparation for disabling it, and each possibility carries vastly different implications. Cyber intrusions into nuclear-adjacent command networks might be exploratory or preparatory. Still, in a compressed decision-making environment, the time to verify is the time when the risk of escalation is highest. In this context, speed is a double-edged sword: acting too slowly risks conceding the initiative, but moving too quickly risks triggering a spiral that neither side intended.

Taiwan’s counters

Taiwan is not passive in this story. While its defensive doctrine is built around absorbing the opening blow, its counter-offensive options aim to impose costs on the PLA from the moment the first move is detected. The obvious starting point is dispersal. Aircraft are moved onto roads and remote strips, mobile launchers shift constantly under camouflage or decoy covers, and relocation drills are rehearsed so often that they can be executed under fire. Dispersal is not only about survival. It is about creating uncertainty for PLA planners, forcing them to allocate more missiles, more reconnaissance assets and more time to find fleeting targets.

At sea, Taiwan can use its fleet of fast attack craft, minelayers and unmanned surface vessels to threaten landing corridors. Sea mines, deployed covertly in advance or seeded by air and drone during the conflict, can channel or delay amphibious forces. Coastal missile batteries with Harpoon and Hsiung Feng anti-ship missiles can turn choke points into ambush zones, especially when paired with decoys to draw PLA counter-battery fire. The aim is to make the water between the mainland and Taiwan a contested space where every approach route carries risk.

In the air, Taiwan’s fighters may be outnumbered. Still, they can be tasked for selective offensive sweeps against exposed PLA support assets such as tankers, airborne early warning aircraft or maritime patrol platforms. Removing these high-value enablers degrades the PLA’s ability to sustain tempo over the strait. Unmanned aerial vehicles, both military and civilian-adapted, can be used aggressively for reconnaissance, loitering munition strikes and electronic warfare. Air defences that remain mobile and unpredictable can continue to exact a price on any PLA aircraft operating over Taiwan or its approaches.

In cyberspace, Taiwan has the capacity to disrupt PLA command, logistics and propaganda networks. Offensive cyber units can target shipboard systems, navigation data and regional information operations hubs. Cyber attacks timed to coincide with kinetic strikes can multiply the effect, making recovery slower and more costly. Even limited offensive cyber actions against logistics management or port operations on the Chinese coast could complicate PLA sustainment plans and slow the pace of an assault.

Space is another contested arena. While Taiwan does not operate large constellations, it can collaborate with allied commercial providers to rapidly replace degraded intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance feeds. It could also employ electronic warfare systems to interfere with PLA satellite communications and navigation signals within its battlespace. Denying or degrading the PLA’s space-based targeting and navigation reduces the precision of its missile strikes and slows its operational tempo.

Civil defence remains a force multiplier. Hardened shelters, decentralised medical facilities and pre-distributed supplies ensure that military resources are not pulled entirely into humanitarian relief. Civilian volunteers trained in reconnaissance, drone operation and emergency communications can extend the reach of the armed forces, acting as spotters for artillery or missile strikes. This citizen-based intelligence gathering, if coordinated effectively, could help plug gaps in formal surveillance and create a constant stream of targeting data.

The Ukraine lesson is that commercial space is powerful but political, and reliance on any single private network is a vulnerability. Taiwan’s strategy anticipates outages and includes sovereign and allied satellite communications as fallback options. Small, smart munitions that complicate landings and slow logistics are cheaper and easier to mass-produce than high-end platforms. When paired with distributed sensing from drones, passive radar or even crowdsourced optical networks, they can make every square kilometre of coastline a potential kill zone. None of this guarantees repelling an invasion, but it transforms the opening weeks from a rapid advance into a grinding, attritional contest. The longer Taiwan can deny Beijing a quick victory, the greater the chance that allied intervention will arrive with force sufficient to shift the balance.

US and Allied Response

When allied intervention comes, it focuses on speed, disruption, and survivability. By 2030, the United States and its partners are expected to field a new generation of long-range strike capabilities, advanced unmanned systems, and improved integration across air, sea, space, and cyber domains. The opening hours are about buying time for Taiwan by contesting the landing zones and breaking the momentum of the PLA’s initial push. Forward-based aircraft and naval assets disperse rapidly to complicate targeting, while strike packages form at range, ready to engage high-value Chinese assets the moment an opportunity presents itself.

Long-range bombers, potentially including operational B-21 Raiders, would provide deep-penetration strike options against Chinese staging areas, missile batteries, and forward air bases. Their stealth and payload capacity would make them valuable for precision strikes on hardened targets supporting the invasion. Carrier air wings, operating from the edges of China’s anti-access missile envelopes, would launch both manned and unmanned strike missions aimed at amphibious groups, escort vessels, and logistics ships. Improved drone capabilities, ranging from high-end stealth UCAVs for deep-strike to swarming systems for saturation attacks, would help overwhelm Chinese defences and force the PLA to divide its attention across multiple threat axes.

Under the surface, allied submarines would play a critical role. SSNs and SSGNs, already on station in the Philippine Sea and the South China Sea at the onset of the crisis, would hunt PLA surface combatants and target amphibious transports before they could reach Taiwan’s coastline. Their ability to operate covertly inside contested waters would also allow them to strike at Chinese logistics lines and deploy smart mines in key approaches. Special operations forces could be inserted onto Taiwan or into nearby contested islands to coordinate strikes, disrupt command facilities, and provide targeting data for long-range fires.

Cyber and space would be active theatres for the allied response from the outset. Offensive cyber campaigns could be directed at Chinese logistics software, port operations, and command networks to slow the tempo of the invasion. Space-based ISR would prioritise tracking amphibious movements and monitoring missile deployments, ensuring allied forces can adapt their targeting in real time. Cooperation with commercial satellite operators would be essential to maintain resilient communications and imagery, even under heavy Chinese counterspace pressure.

The strategic aim in the first seventy-two hours would not necessarily be the wholesale destruction of the invasion force but the imposition of enough attrition, disruption, and uncertainty to force Beijing into a prolonged, high-cost campaign. By stretching Chinese supply lines, eroding their ability to sustain air cover over the strait, and holding key assets at constant risk, the United States and its allies would seek to collapse the timetable that Beijing relies on for a quick victory. In a conflict measured in days, the difference betwee

The economic theatre

Even if shots are limited, the economic shock is not. Global supply chains are ill-equipped to absorb risk when the risk is systemic and sits astride one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes. Insurance rates spike for vessels anywhere near the conflict zone. Some shipping reroutes immediately away from contested waters, while others linger and risk seizure or blockade. Air routes shift, adding hours and cost to cargo flights.

Semiconductor supply becomes a daily political drama. Taiwan’s fabs supply chips that underpin everything from smartphones to military systems, and even a temporary halt in exports could ripple into global production lines within weeks. Stockpiles exist, but they are shallow. Policymakers scramble to stabilise markets, negotiate priority access for critical sectors, and coordinate sanctions without triggering further supply crunches.

Sanctions against China are not like sanctions against Russia. The interdependence is more profound, with China embedded in countless consumer and industrial supply chains. Sanctioning key Chinese exports can send inflation spikes through economies already under pressure. Beijing knows this and will likely have pre-wired buffers, currency reserves, commodity stockpiles, and alternative buyers in non-aligned states, to ride out the initial hit.

Markets react instantly to risk signals, and the political pressure to “calm the markets” can shape military and diplomatic choices. In the background, companies quietly rediscover the dull heroism of inventory, holding more stock than efficiency models recommend simply to survive geopolitical turbulence.

Law, governance, and the space mess

The 2030 fight forces a reckoning in space law and norms. There is still no binding international rulebook for close-approach operations against commercial satellites carrying national traffic, nor for when cyber activity against satellite ground stations constitutes an armed attack. The Outer Space Treaty assigns responsibility for national actors, including private firms, but was written in an era when the idea of private mega-constellations was science fiction.

Ukraine’s experience already prompted debate about the legal status of commercial providers in war. A Taiwan crisis would turn that debate into urgent policy. Would a commercial constellation supporting a nation’s defence be considered a legitimate military target? If so, what protections or compensations would apply?

The pragmatic answer is resilience arranged in advance. Governments cannot assume a single private network will remain available when politics heat up. Nor can they easily replace the capacity of the largest LEO constellations at short notice. Allied agreements on data-sharing, orbital slot coordination, and reciprocal use of sovereign systems would add insurance.

The governance question extends beyond war. The aftermath of an on-orbit attack, even one short of destruction, could leave debris fields in critical orbits, threatening global space access for years. The legal frameworks to attribute responsibility, manage compensation, and coordinate cleanup are immature. Without them, post-crisis recovery could be as politically fraught as the conflict itself.

The escalation trap

The nuclear threshold remains high, and no rational actor seeks to climb that ladder. Yet the nature of integrated warfare compresses timelines and strips away context, creating precisely the conditions in which miscalculation becomes more likely. In a multi-domain fight, space, cyber and electronic warfare operations are often invisible to the public and even to some decision-makers. This makes intent harder to read and leaves greater room for dangerous assumptions. Actions designed as defensive preparation can be interpreted as offensive escalation, particularly when they affect critical systems linked to nuclear deterrence.

Dual-use satellites and dual-capable missiles add another layer of ambiguity. A satellite that typically performs weather monitoring could be re-tasked to gather intelligence on missile launch sites. A ballistic missile launcher could be configured to fire either a conventional or a nuclear payload. In the heat of a fast-moving crisis, adversaries may not have the time or the technical means to determine which role is in play before deciding how to respond. The same uncertainty applies to missiles such as the DF-26, which can carry either payload type, forcing an opponent to assume the worst in a situation where seconds matter.

Cyber operations create their own risks. Penetrating or disrupting a command-and-control network could be intended to degrade conventional military coordination. Still, if that network is also connected to nuclear early warning or launch authority systems, the intrusion may be perceived as a precursor to a nuclear first strike. This danger is magnified in an environment where leaders already expect adversaries to act pre-emptively and where the line between conventional and strategic systems is thin. The same malware that blinds an air defence network could, if misinterpreted, be seen as disabling the very systems that protect a state’s nuclear forces.

Reducing these risks requires more than good intentions. Reliable crisis communications, including direct hotlines between military commands, can provide a way to clarify actions before they spiral out of control. Pre-negotiated redlines for the treatment of commercial space assets could prevent attacks on infrastructure that carries both civilian and military traffic. Regular habits of contact between senior military officers on each side can help ensure that when a message is sent, it is received by someone who recognises its purpose and authority. Military-to-military familiarity cannot guarantee restraint, but it can create vital channels for reassurance in moments of uncertainty.

None of these measures can remove the danger entirely, but they make it less likely that a counterspace manoeuvre or a garbled radar feed will be mistaken for the start of a strategic attack. In the compressed decision-making environment of integrated warfare, buying even a few extra minutes for verification and de-escalation can make the difference between a contained crisis and an irreversible escalation. In a Taiwan scenario, where space, cyber and maritime activity would all spike simultaneously, those minutes could be the thin line between coercion and catastrophe.

How this war could end without an invasion

The title is not a trick question. China does not need to plant a flag in central Taipei to change Taiwan’s trajectory. A prolonged blockade, backed by selective strikes on key infrastructure, can grind an island economy into contraction and sap public confidence. Unlike an amphibious assault, a blockade can be dialled up or down, applying steady pressure without the political and operational risks of large-scale landings.

A partial seizure of outlying islands such as Penghu, Kinmen or the Pratas can change facts in slow motion. These moves present the world with a dilemma: escalate in defence of small, sometimes sparsely populated territories, or accept the fait accompli in the hope of avoiding a wider war. Each acceptance becomes a precedent, normalising incremental change in the status quo.

The coercive strategy does not require complete physical control. A campaign that begins with blinding and isolation, disabling critical satellites, jamming communications and disrupting civilian systems, can be sustained through maritime interdiction, air patrols and cyber harassment. The objective is to impose a sense of inevitability in Taipei that further resistance will only deepen economic pain and strategic isolation.

Such a campaign can end at the negotiating table under terms set by Beijing, without a single PLA soldier marching through the Presidential Office Building. The question for democracies is whether they can sustain the political will, public attention and economic resilience needed to make such coercion fail. The answer will depend not just on military capability but on how much short-term pain governments are willing to absorb for a long-term principle.

External actors

A Taiwan crisis in 2030 would not unfold in a vacuum. China’s closest partners would not need to join the fight directly to alter the strategic balance.

Russia, still in a prolonged confrontation with NATO, could exploit the distraction to intensify pressure in Europe. This could range from increased military exercises near NATO borders to cyber operations against European infrastructure. Even without firing a shot, such activity would force the United States and its allies to divide attention and resources between two fronts. Moscow might also deepen arms and technology transfers to Beijing in the run-up to a crisis, particularly in areas like missile propulsion, air defence, and electronic warfare.

North Korea remains an unpredictable but useful lever for Beijing. A sudden missile test series, an artillery provocation along the Demilitarised Zone, or renewed nuclear brinkmanship could tie down U.S. and South Korean forces at a critical moment, complicating the wider allied response. The possibility of simultaneous crises in the Taiwan Strait and on the Korean Peninsula would be a powerful deterrent against rapid U.S. escalation.

Other states with pragmatic ties to China, such as Iran, could apply indirect pressure by disrupting maritime routes elsewhere, engaging in cyber operations against U.S. partners, or using diplomatic channels to shield Beijing from sanctions and condemnation in international forums. Even limited support from these actors, material, informational, or political, would increase the strain on a coalition trying to respond decisively to a Taiwan contingency.

These moves would not guarantee Beijing’s success, but they would shape the strategic environment. The PLA’s integrated warfare doctrine assumes that shaping starts long before the first move across the strait, and external actors give Beijing more tools to stretch and test allied cohesion.

What to watch now

Three broad trends will likely shape whether a 2030 Taiwan scenario becomes more probable. None of them, on their own, are definitive warnings of imminent conflict, much like increased Russian military exercises near NATO borders have not automatically signalled nuclear escalation. Instead, they are cumulative indicators that, when seen together and sustained over time, suggest a shift in capability and intent.

- First, in space, watch for a steady pattern of close-proximity manoeuvres and orbital adjustments, particularly those involving satellites with plausible counterspace roles. Isolated incidents may be routine testing or debris avoidance. A sustained pattern, especially involving dual-use assets in key orbits, would suggest rehearsal for interference or denial missions.

- Second, at sea, track the pace and scale of expansion in landing and heavy transport capacity. This is not about a single new class of vessel, but about whether the overall amphibious and sealift fleet is growing in ways that make large-scale cross-strait operations more feasible. Auxiliary ships, merchant conversions, and logistics infrastructure ashore are as telling as purpose-built landing craft.

- Third, among allies, note tangible movement on pre-positioning supplies, expanding regional access points, and deploying long-range strike capabilities to positions that could realistically shape a Taiwan contingency. Exercises, base upgrades, and bilateral agreements can matter as much as headline deployments.

Individually, these developments can be explained away as routine modernisation or prudent hedging. Together, they alter the balance of opportunity, shifting the strategic calculus for both deterrence and coercion. The signal is in the trend, not the isolated headline.

Closing reflection

The first sign was a picture, because that is how modern crises start. We see them before we name them. What follows is a contest to shape perception and tempo across domains that once sat in the background. Space. Networks. Logistics. In 2030, these are decisive arenas. The danger is not only what an adversary does, but how quickly those actions compress the time available for others to respond. Decisions that once took hours now need to be made in minutes, often with incomplete or contradictory information. That is how mistakes happen.

Avoiding this outcome will require more than military deterrence. It means closing the political, economic and geosecurity gaps that adversaries will exploit years before a shot is fired. The United States and its allies must align rules of engagement for emerging domains like cyber and space, clarify red lines for attacks on commercial infrastructure, and exercise these responses regularly to remove ambiguity. Intelligence sharing must move from episodic to continuous, with joint monitoring of indicators that would precede coercion or invasion. Logistics chains, from fuel storage to semiconductor supply, must be hardened and diversified, even when it costs more in the short term.

Resilience is as much about psychology as it is about infrastructure. Adversaries succeed when they create doubt, delay and division. That means allied governments must communicate their commitments clearly to their own publics and to each other, so that decisions in a crisis are rapid, coordinated and credible. This requires diplomacy that deepens trust, economic policy that reduces dependence on hostile actors, and security cooperation that is designed to work at operational speed, not just on paper.

If peace is to hold, preparation cannot be left to the margins of defence budgets or the back pages of strategy documents. Build redundancy into the systems we depend on. Establish thresholds in advance, so no leader has to guess where the line is. Test the mechanisms of alliance in real conditions, not just in wargames. Invest in the quiet, unfashionable infrastructure of resilience, because in a crisis those extra minutes to verify, decide and act may be the difference between stability and disaster. In an era when speed is a weapon, those minutes could be the most strategic asset we have.